Imagined Journeys

As a companion project to Diary of a Piece of Driftwood, I let my imagination ramble further.

After studying oceanography texts, I made semi-educated guesses at where the piece of driftwood might end up.

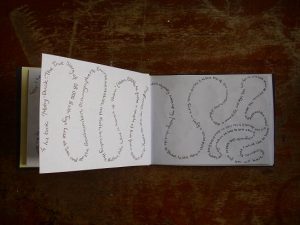

I made maps of these potential journeys.

The maps show no scale:

- They are ambiguous

- They are imaginary

- They are fictional

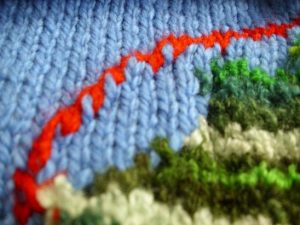

The knitted map is still on the needles; unfinished.

You can see the journey of the strands, winding themselves into oceans and land masses.

They could carry on their journey, or unravel and fall apart as if it never happened.

Did it happen?

Maybe it will happen.

The next stage would be to cast off the stitches.

In knitting, casting off means that the work is finished.

Casting off means no more knitting.

I decided not to cast off the stitches.

How do you know when a journey has ended?

Is it when you stop moving?

Is it when someone marks it on a map?

Is this an end or a resting point?

A new starting point?

A nothing point on an illusory map?

The sea is fascinating because it is unknowable.

It is incomprehensibly vast, yet when compared to the solar system, or the galaxy, or the universe, it becomes incomprehensibly small.

Scale is subjective;

I played with this subjectivity when making the maps.

Usually we think of long journeys as more significant than shorter ones.

I inverted this, and depicted the shortest journey, (a few metres), on the largest map, and the longest journey (thousands of miles), on the smallest.

The longest journey could be seen as the most epic, because of the distance, or the most futile because the driftwood becomes trapped in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

This is a dead-end for currents where vast amounts of debris become stuck and cause problems for wildlife, and ultimately, us.

Currents are transient.

You cannot map them like you map roads and continents, but people try anyway.

Some currents stick around long enough to be given names like the ‘Gulf Stream’ or ‘North Atlantic Drift’.

Most currents last for hours, or days, or minutes, but we don’t give those ones names;

Not because we don’t want to, but because we can’t.

There are too many of them.

I’ve read about neap tides and spring tides and Ekman Transport and the Coriolis Effect.

I’ve learnt about eddies and gyres and the Global Conveyor Belt and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

My findings can be summarised like this:

The ocean is really, really complicated; more complicated than I can comprehend.

It is so complicated, that even oceanographers don’t understand what it is doing or why it is doing it a lot of the time.

I like it this way.